During the reign of Henry II, William de Lancaster made a grant that would eventually help to shape Stalmine. William gave Hugh Garth, a hermit, “the place Askelcros and Crok, with his fishery on the Loyne, to maintain a hospital.” Loyne became Lune and, whilst there is a Crook Farm and a Crook Cottage on Thurnham Moss, no-one knows who Askel was, let alone why he had a cross.

Hugh received further grants, and then the mother-house at Leicester gave leave for the construction of an abbey which, in 1190, Pope Clement III decreed should be called the Monastery of St. Mary of the Premonstratensian order of Cockersand. In time, the monks of Cockersand built chapels at Stalmine, Pilling and Hambleton, Stalmine’s being built in 1240.

Stalmine is one of the very few places that retains the spelling it had in the Domesday Book, which is quite something when you consider that Garstang was Cherestanc. Stalmine’s name stems from Old Norse and Old English words meaning ‘land by the mouth of the river.’ There were times when it became Staumin and some dyed-in-the-wool locals still call it that. But think of ‘talk’ and ‘walk’ and particularly ‘stalk’ – perhaps the true pronunciation of Stalmine is Staumin. So the ones who call it that are not the country yokels some take them to be, they are probably correct and are keeping history alive.

In the past, Stalmine really was by the mouth of the river and was much larger than the village we know today. It encompassed a hill covered with brushwood and Hakin’s mound. These two spots became known as Preesall and Hakenshall, their names stemming from the Celtic, Old English and Old Norse words that described the locations.

It seems likely that the monks built their Stalmine chapel where our church now stands; a high drumlin standing clear of the undrained land would have been the most sensible site. The monks almost certainly came to the area by boat; a track up from the river is still known as Monks’ Lane. It would have been difficult for them to travel by land; the roads would have been muddy or dusty and the bubbling morass known as the Blackelache – the Black Lake – now Pilling Moss – was difficult to get round.

Long before the monks’ time, Stalmine was known to the Romans for they undoubtedly had a port at Wardley’s. A Roman road ran east from there through Nateby to join the main south-north road at Cabus. Another road ran north and it is claimed that this later became a King’s Highway of some status. This is the lane we now call Highgate Lane, which becomes Back Lane at the boundary with Preesall. In recent years, a careless Wyre Borough Council has wrongly signed Highgate Lane as going past Height o’th Hill Farm, thus wiping out two thousand years of history and making life difficult for visitors following historical evidence. The site of what is thought to have been a century watermill has been made particularly hard to find.

By the 1700’s, boats from all around the Northern Hemisphere were arriving at Wardley’s. It and Skippool together had more trade than Liverpool. Despite its important port, the world seems to have largely passed Stalmine by. In 1651, however, Earl Derby and a few hundred of his men sailed in and passed through on their way from the Isle of Man to support Charles II in his attempt to wrest his kingdom back from Cromwell. This attempt ended with Charles hiding in an oak tree and the Earl being beheaded in Bolton.

Other countrywide events made more of an impact. The Reformation in 1534 was obviously one. By that time most, perhaps all, of Stalmine had been bequeathed to Furness Abbey. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries, which began in 1536, it became the property of the Crown, or, put more simply, Henry VIII grabbed it.

Another happening was the Plague. In the church register covering 1623, the Parish Clerk noted: “There was buried the tyme that I were sick fortie and above or thereabouts at the parochiall church at Stalimin within the year above written.”

During those years, Stalmine did not always – perhaps, ever – have a resident priest. The piece below is a seventeenth century commissioners’ report on Stalmine. I have not translated it in case I got some of it wrong.

“Certain Parishens and Tenants on an Iland complayne that thei oftymes have their freynes dye without Rights of the Churche, becaus thei be oftymes closed in with the see that no man come to them, and therefore thei desyre that where the Viccer doth fyne a Priest to syng at the Chapell within the said Iland every Sonday and Haliday that the said Priest might contynually abyde among them, and they wold to thei Power, bere a ley towards his Salary if my Lady and the Viccar would bere some charge with them.”

Have you worked it out? It was a plea for a resident priest so that people did not die without Church Rites. Note that Stalmine was described as an Iland – an island – an Iland surrounded by the River Wyer, the Bay of Morecambe and the Blackelache. I have no idea who ‘my Lady’ was.

Following the Civil War, the extreme Reformists embarked on the destruction of Popish or idolistic symbols. They even destroyed churchyard crosses but many churches acted ahead of them by modifying their crosses into sundials. The sundial by the St. James’ church porch is made from an inverted cross shaft but it is dated 1690, by which time the Reformists had lost their power. Did a shattered cross lie in a hedge-side for thirty years or more?

After the Reformation, Stalmine’s church became Presbyterian in its outlook and it remained that way for centuries. As recently as the 1960’s, a churchwarden reproached a visiting vicar who had prepared for communion in his customary way, facing the altar. He was told that vicars should stand at the end of the altar, which was an almost forgotten widespread custom that allowed congregations to see that vicars were not undertaking papist practices. It is interesting to note too that it is only in recent times that the choir has begun to wear robes again. These two facts alone indicate that, for a long time, Stalmine’s Presbyterian attitude was unwavering.

Returning to the subject of burials, Stalmine’s churchyard was consecrated in 1236. Although it is small an amazing number have been buried there. The church registers from 1583 to 1724 were published several years ago. There are gaps in these registers but there is sufficient to indicate that over 3,000 people were buried in Stalmine during those 141 years alone.

Burials became an increasing problem for churches and resulted in the land around many becoming higher than the church itself this is still evident at some village churches. In extreme cases, bodies were buried in land above the level of the surrounding area which, without going into too much detail, must have made walking by them taxing. Stalmine does not seem to have had major troubles but, nevertheless, a new cemetery was opened down Cemetery Lane in 1856. Another local puzzle is: ‘What was Cemetery Lane called before there was a cemetery?’ The most likely answer is: the lost Kirkgate.

Surprisingly, an appreciable number of burials still took place in St. James’ graveyard until 1899. Even more surprisingly, there seems to have been no strict selection policy since the burials included a “man washed up by the sea.” I have often wondered how poor, young couples managed to set up home together. The old registers suggest that some of them probably did not and had to remain unmarried – the christenings in the registers list many bastards. As many as fourteen out of fifty christenings in one year carried such a mark. No doubt these were a result of lovers’ strolls through the fields. I expect that the community was understanding. I doubt though that it was understanding of Mrs Margt Stanley, whose daughter Catherine was begotten by Mr Charles Standish.

If you would like to read more of this, visit Knott End Library and ask for ‘The Registers of the Parish Church of Stalmine’, by the Lancashire Parish Registers Society. You will be able to see if any of your local relatives were recusants – devout Roman Catholics when that was not a good idea – for they were buried at night.

Now about more cheerful things. In olden times, churches used to renew the rush coverings on their earthen floor. This was an important annual event and it took place on a holy day – a holiday. The day chosen was the Saint’s Day associated with the church, namely the saint the church was dedicated to. Stalmine church used to be dedicated to St. Oswald and so this event was held on his day, August 5th. The event grew into a big occasion and became known as the Tosset Feast. Tosset is said to be a corruption of St. Oswald but I am not convinced. Would people have dared to be so disrespectful? An identical ‘corruption’ occurred as far away as Somerset and their records carry a list of saints all renamed with T as an initial; for instance, St. Aidan was Tathan. In 1656, Cromwell’s Puritan parliament abolished archbishops and bishops. Were saints abolished or frowned upon at some time of religious intolerance? After all, they were created by the Pope. And did that lead to words like Tosset being used as a way round the law? No-one seems to know.

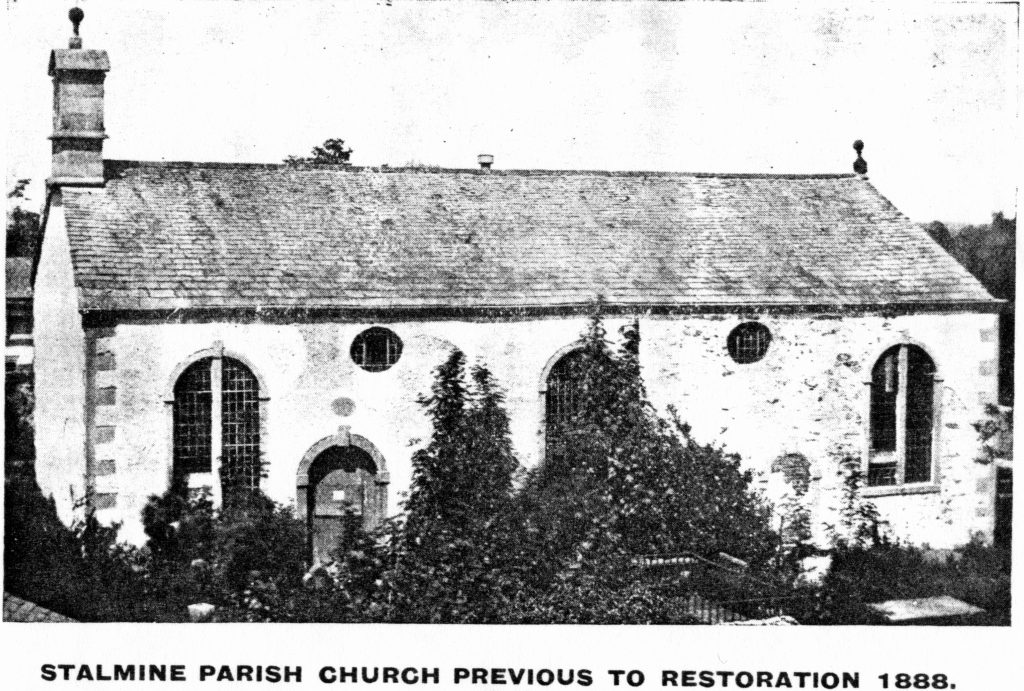

Stalmine church was rebuilt in 1806, although the chancel, vestry, sanctuary and organ only date from the late 1800’s.

It was made a Grade II listed building in 1999. The 1806 rebuilding was largely funded by the Lord of the Manor, James Bourne, and it was rededicated to St. James. Even so, St. Oswald’s Day – the Tosset Feast – was still celebrated. A special sugar-covered, spicy shortbread biscuit called a Tosset Cake was eaten on this day. Special cakes used to be a feature of religious days; indeed, we still have pancakes, Simnel Cakes, Hot Cross Buns and Christmas Cakes.

The well-know “Blackpool Evening Gazette” country writer, R. G. Shepherd, wrote about the Tosset Feast several times, saying that it was still a big event in his father’s day – up until the First World War. Among the tales his father told him was one about a tightrope walker who crossed the road from the Saracen’s Head to the Roundhouse. Of course, those places are in Preesall and that is where the Shepherds lived. Preesall was still in Stalmine’s ecclesiastical parish in those days, but that would soon change.

Preesall grew rapidly after salt was found there in 1872. This growth led to a demand for a more local church to be built. The Stalmine villagers resisted this for some time, obviously objecting to being told what to do by ‘foreigners’ who had come from Cheshire to mine salt. Knott End was growing too and so eventually, in 1899, a new church was built at Preesall – and St. Oswald re-joined the Over Wyre flock. This church was a missionary church, which meant that the likes of weddings could not be held there. It eventually became independent in 1934.

The boundary between the ecclesiastical parishes was set as being along Cartgate. No doubt this was done so that Stalmine kept the then vicarage, opposite Fernhill, a hundred yards south of Cartgate. I suppose that this means that since St. Aidan’s Technology College – which dates from 1963 – is a Church of England school it is correctly in Stalmine.

A major change occurred in St. James’ churchyard in 1973. Until then it was full of higgledy-piggledy grave stones which, although quaint, did lead to an untidy appearance with grass and weeds growing round them. The decision was made to remove them, clean them and build them into a new south wall. This has the second benefit of making them easy to read, although reading them does present us with a disturbing catalogue of infant mortality.

A casual visitor to the churchyard may not realise that there is a war memorial there, although everyone walks by it as they enter. This memorial is the flagpole by the gate and it has a plaque at its base which reads ‘Dedicated to the memory of all those from Stalmine with Staynall who have given their lives in defence of the freedom of their country.’ This flagpole was donated by the Parish Council so that the church could fly a flag on behalf of the village on Remembrance Day and on other significant occasions. The funding for the pole was raised at a party organised by the Council in 1995; fittingly, this party was held as a celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of VE Day. There are also two slate wall-plaques inside the church in memory of the men who laid down their lives in the two World Wars. Twenty-three men from the First War and four from the Second are named as having made the ultimate sacrifice.

Yet another change occurred within the graveyard in 2007 when a large, two-storey meeting room was added to the church. This was no small matter since all the land around the church contained graves and some parishioners objected to their ancestors’ graves being built over. Because of these objections, a Consistory Court had to be held and that court eventually gave permission to build.

So, Stalmine’s church has seen many changes. Two of the biggest have occurred quite recently and involved people rather than the church fabric. As we all know, the end of the twentieth century saw moves being made to give women leading roles in the Church of England. We know too that these campaigns were not without controversy. In 2001 Dyllis Dickinson was appointed as an Ordained Local Minister to work in our parish. Dyllis was one of the first such people in the Blackburn Diocese and everyone accepted her without question; it possibly helped that she was a local lass, born and bred. Perhaps there would have been dissenting voices if she had followed the salt miners from Cheshire!

Another change occurred in 2000 when St. James’ became a united benefice alongside the parish of St. John the Baptist at Pilling with St. Mark at Eagland Hill. Then, in 2011, they began to share their vicar with the Waterside Parishes of Hambleton, Out Rawcliffe and Preesall. Subsequently in 2020 the five parishes were united as the Over Wyre benefice, and became one ecclesiastical domain for the first time since the days of the Cockersand Abbey monks. Father Andy Shaw was the first person to be tasked with taking all of this area under his wing.

To end I will go back to the beginning. As we have seen, Stalmine’s church story began in 1240, but Christianity started long before then and other religions before that. The Celts looked upon the yew tree as being sacred. Some say that they allowed anyone standing by a yew to speak as they wished without fear. If this is true, Christian missionaries would have stood by one to preach God’s word. The natural outcome would be that churches were built alongside yew frees and five hundred English churches do stand by a tree that is older than itself. There is no record of our church ever having had a yew tree but many people remember one that stood close by until it was cut down not long ago.

Since the Millennium celebrations were about two thousand years of

Christianity, the Church of England supported a Conservation Foundation scheme acknowledging the yew tree’s religious connection. This scheme offered towns and villages the gift of ‘A Yew Tree for the Millennium.’ Stalmine accepted the offer and its Tree Warden was given a young tree at a ceremony at Myerscough College. This free had been grown from a cutting taken from an old yew that dominates the churchyard of the thirteenth century church of St. Mary on Hampshire’s Hayling Island. This yew is thought to be two thousand years old — it may be the oldest in the country – and its offshoot is now growing at St. James’.

If by chance you are a parishioner reading this a hundred years from now, admire the magnificent yew and think of us but, above all, enjoy your life in Stalmine and at St. James’.

Bevan Ridehalgh.

Anno Domini MMXII

(Slightly adapted and updated PEB MMXXI)

Printed copies of this history may be obtained free of charge at church.